Go Manual

One Pilot's Perspective on Autopilot

In my time as a Naval Aviator, I flew one jet with a crappy autopilot, one jet with an exceptional autopilot, and one jet with no autopilot at all. As a Landing Signal Officer (LSO) I enjoyed the agony and ecstasy of waving more than 25,000 carrier landings, many of which used some sort of autopilot assistance. Most passes were safe, some were ugly, and a few were downright scary. What follows are some of my thoughts on that experience and its implications for enhanced cruise control and self-driving cars.

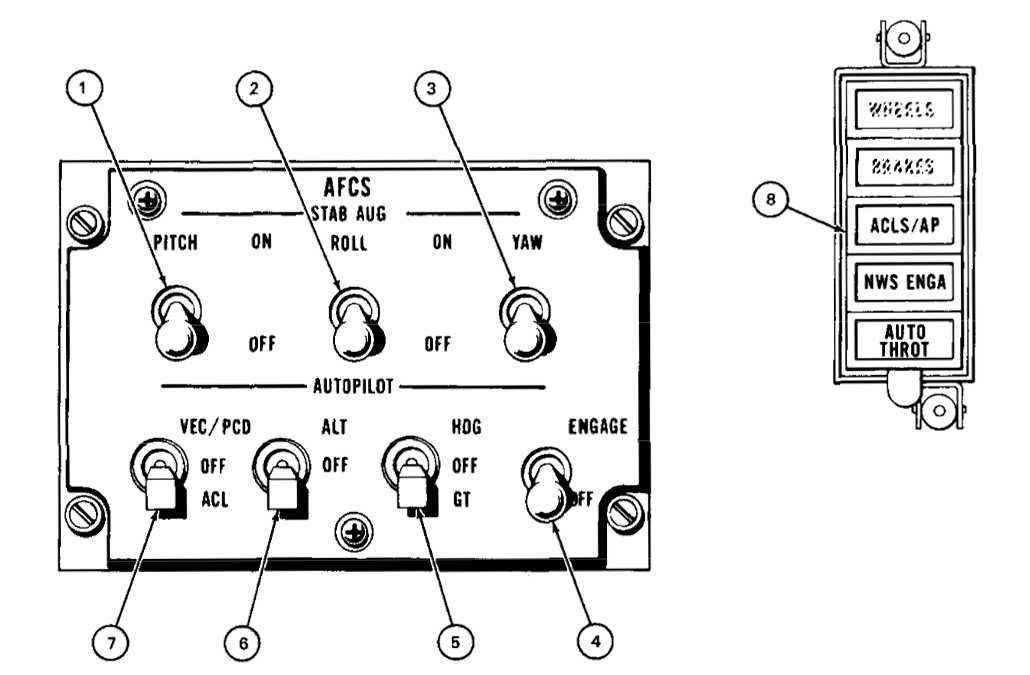

Tomcat AFCS Panel and Ladder Lights

Like Tesla’s Autopilot, there are several “pilot-relief modes” available in modern fighter and transport aircraft.

The simplest is auto-throttle, which is roughly equivalent to cruise control in a car. At altitude, the pilot clicks a button at the desired speed and the jet does its best to maintain it. In the landing environment, the auto-throttles on Navy fighters hold an optimum angle of attack (AOA), a unit that’s similar to speed but doesn’t vary with aircraft weight.

Carrier landings on auto-throttles can be extremely smooth as long as the aircraft holds a stable flight path. If significant deviations in glideslope or lineup occur, most experienced pilots will disengage auto-throttles, fix their pass, and land, often without the LSOs even noticing. Inexperienced pilots will occasionally try to ride it out in auto, which commonly results in a bucking jet, pilot-induced oscillations, an annoyed “Go Manual!” call from the LSO, and maybe even a wave-off.

Next in complexity are the various modes you probably think of as conventional “autopilot” – they let you pick an altitude and/or course for the airplane to hold. They’re fairly simple to use and usually engaged during the stable cruise phase of flight.

The third and most complex mode is “auto-land”. Specially certified airliners and crews use their aircraft’s autopilot, GPS, and Instrument Landing Systems to touch down safely on a runway with as little as 150 feet of visibility.

On Navy fighters, the Automatic Carrier Landing System (ACLS) couples the jet’s autopilot to a high-resolution shipboard radar via datalink. Using these components, ACLS can bring a jet all the way down to an arrested landing in near-zero visibility without any further input from the human at the controls.

Finally, most modern airliners have full-blown flight management systems (FMS), which can fly an entire pre-planned route, from just after takeoff, through climb, cruise, descent, approach, and landing. Every day, thousands of airline crews safely carry passengers to their destinations all over the world while handling the flight controls a mere fraction of their time in flight.

One day when I was Force Paddles an interesting proposal crossed my desk. Naval Aviators spend a LOT of time practicing how to land at the boat, both ashore and at sea. This requires a fair amount of resources (airframe life, fuel, pilot hours, days at sea) and generates a decent amount of noise for those living near the airfield. Many entities in and out of Naval Aviation try to reallocate (steal) those resources whenever they get the chance.

The proposal in question suggested that making automated landings standard for carrier recoveries might reduce the overall requirement for Field Carrier Landing Practice and at-sea carrier landing currency flights. My counter-intuitive response was “No, we’d probably have to do more of them”.

Why? Because landing at sea is the hardest thing we do, and every hand-flown landing makes the next one a little better. We weren’t practicing hundreds of landings with the easy ones in mind. We practiced hundreds of landings so we could survive the hard ones. Take those landings away, and the risks go up substantially.

Once manual control becomes an emergency, then actual emergencies become that much more dangerous. Even the most reliable autopilots can break. ACLS is often unusable in heavy rain, when the deck is pitching, or when the aircraft experiences an engine failure or flight control issue. When one or more of those things inevitably happens, you’d better hope you’ve practiced, because a successful landing is completely in your hands.

At the end of the day, the cost of all that practice is far lower than the cost of a broken machine and its dead occupants. The aviation community has learned this lesson firsthand, and now it’s time for the driving public to learn it as well.

Autopilots can create a sense of complacency that (left unchecked) leads to atrophy in basic driving skills. Worse, they allow your attention to atrophy. If 99.99% of the time I don’t have to watch my vehicle closely, what are the chances I’ll be watching the 0.01% of the time I’m required to make a split-second decision that will save the day? What are the chances I’ll have the context in that moment to choose the right action?

Unlike airplanes, cars spend the vast majority of their time in close proximity to other objects, in an environment that is inherently more difficult to predict. Only in the last few decades have civil aircraft been able to reliably land themselves, and that’s on empty runways that are 150 feet wide and over two miles long.

Like any complicated computer interface, an autopilot can act in non-intuitive ways, leading to surprising results. Different autopilot modes can change the way a vehicle reacts, and making the mistake of thinking that one or more of those modes are or aren’t enabled can mean the difference between life and death.

Here are just a few examples:

- Eastern Flight 401, 1972: Captain inadvertently disengaged the autopilot while the crew investigated a faulty indicator light on the Lockheed L1011, resulting in a slow, unnoticed descent and eventual impact into the Florida Everglades. 101 fatalities, 75 injured.

- Air New Zealand Flight 901, 1979: A pre-flight change to the FMS flight plan wasn’t communicated to the aircrew resulting in the aircraft flying itself into the side of Mt. Erebus in Antarctica. 257 fatalities.

- Air France Flight 296, 1988: Intentionally disabled auto-throttle protection systems during a demonstration resulted in the Airbus A320 impacting a treeline in Mulhouse, France. 3 fatalities, 50 injured.

- Air France Flight 072, 1993: An autopilot initiated go-around went unrecognized by the crew resulting in the Boeing 747-400 departing the runway on rollout in Papeete, French Polynesia. No fatalities.

- N950KA, 2012: Autopilot disconnected in bad weather leading to the inexperienced pilot troubleshooting the Pilatus PC-12’s autopilot rather than maintaining level flight. 6 fatalities.

- Asiana Airlines Flight 214, 2013: Aircrew incorrectly believed the auto-throttles were engaged on an unstable approach, crashing their Boeing 777 short of the runway at San Francisco International Airport. 3 fatalities, 187 injured.

Autopilots aren’t inherently bad. Quite the contrary, autopilots are fantastic and can be a great way to reduce pilot fatigue and workload. They just come with real consequences and limitations that the folks who build and use them must constantly keep in mind.

Air New Zealand Flight 901

As aviators we learn about the mishaps listed above and countless others like them so we can avoid making the same mistakes. As complex autopilots make their way into cars, we shouldn’t be surprised when average drivers without training make those mistakes as well.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t hold drivers accountable. As a pilot, the responsibility for maintaining currency and situational awareness is wholly mine. That means when things go wrong it’s my fault, not the robot’s. Allowing drivers to abdicate that responsibility is a move that society should avoid at all costs.

That’s the reason I hand-flew all my approaches in the Super Hornet, even though it had great auto-throttles and a finely-tuned auto-land feature. If something went wrong, I wanted to have as much experience as possible and my attention fully devoted to the most difficult part of a carrier aviator’s day.

I expect to approach automotive autopilots the same way. Cars may be inherently easier to drive than an airplane, but occasionally they require every last ounce of your attention and skill to avert disaster.

Cruise control is great, and adaptive cruise control with emergency auto-braking will be an awesome addition to my next vehicle. But I’ll probably stay away from automated steering for as long as my car has a steering wheel.

The robot doesn’t need the practice.