First visit? Start here.

Security expert Bruce Schneier on a new piece from 404 Media:

This feels important:

The Secret Service has used a technology called Locate X which uses location data harvested from ordinary apps installed on phones. Because users agreed to an opaque terms of service page, the Secret Service believes it doesn’t need a warrant.

It’s more important than ever to realize that the vast majority of the devices and applications we rely on each day aren’t made for us.

At its most benign level, our need for entertainment, information, or help becomes a way to create a large geospatial model without our knowledge. For less benign outcomes, take a look at China or consult Orwell.

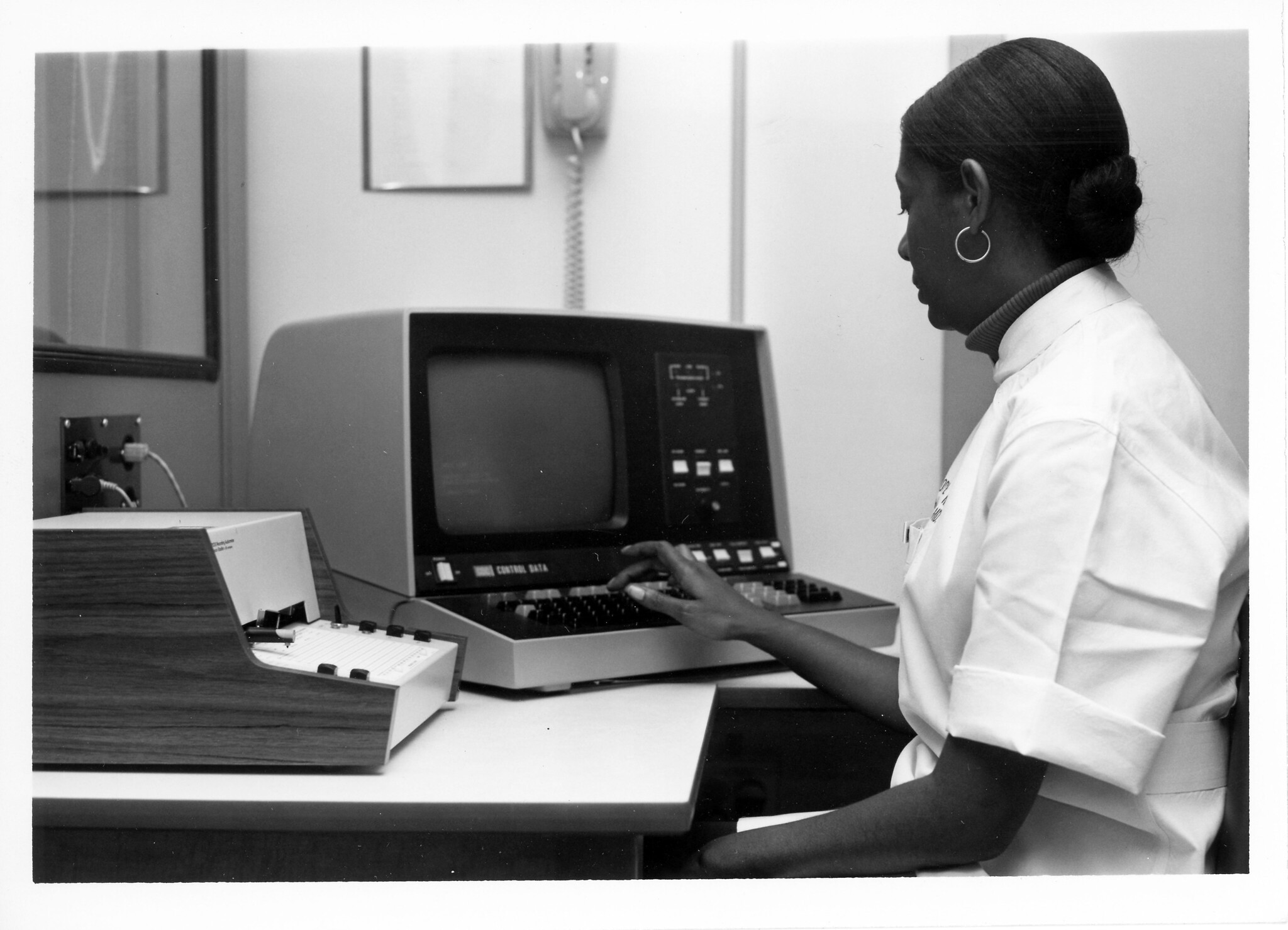

As I dip my toes back into open source software, I’m reminded just how much effort it takes. Disturbingly, I’ve also noticed how much harder it is than before to run open-source operating systems on modern devices. There are so many security barriers baked in at the firmware level that bypassing and disabling them has become a significant challenge.

I urge all of us to consider what you use, how you use it, and who manages those platforms. Embrace the challenge of actively managing your digital environment.

Consider all your platforms carefully. Yes, even Apple.

Moral of the Work

In War: Resolution

In Defeat: Defiance

In Victory: Magnanimity

In Peace: Goodwill

– Winston Churchill, The Second World War

Living in northern Nevada I see a lot of customized and quasi-historical flags that people fly to represent their own particular concept of what America was and should be.

Many of them are variations on the Stars and Stripes that are altered in a way that would have been anathema to conservatives of an earlier age who repeatedly proposed amendments to prevent the desecration of the flag by fire or modification. A popular choice is the Gadsden Flag whose political coopting makes it impossible for me to fly a similar flag with a more naval and noble recent history.

As someone of conscience who sees eerie parallels with the first half of the 20th century in our current state of affairs, I’ve been looking for an emblem of equal historical weight that aligns more closely to how I view the United States, its ideals, and its role in the world.

I can think of nothing more appropriate than the 48-star flag, in use from 1912 to 1959.

Under this flag, the United States:

- Defended Europe against wars of aggression (two hot, one cold)

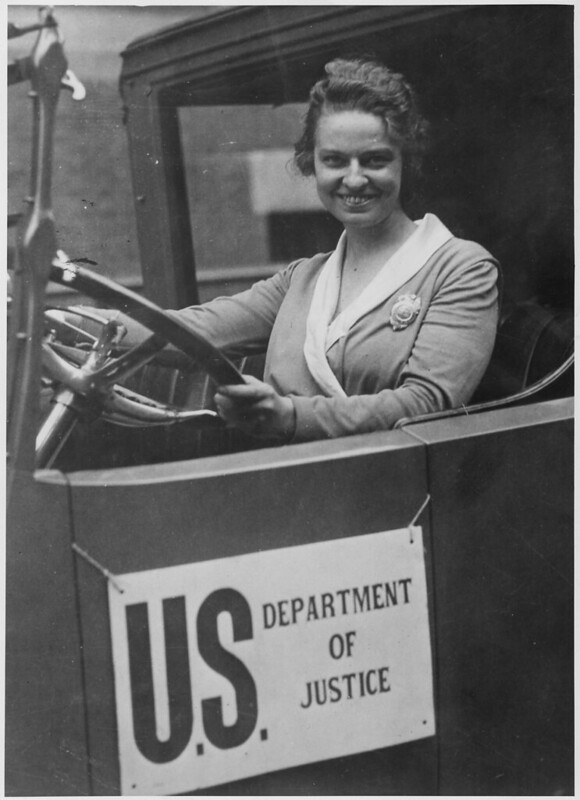

- Finally granted women the right to vote

- Triumphed over the Great Depression with the New Deal

- Sheltered people of Jewish faith and descent, and helped end the Holocaust

- Defeated fascism in Europe and Asia

- Helped found the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations

- Rebuilt and made strong, peaceful, democratic allies out of our former enemies, Germany and Japan

- Rebuilt the rest of Europe, helped it stand against post-war Soviet aggression, co-founded NATO, and conducted the Berlin Airlift

- More than tripled the size of our economy

- Defended South Korea and Japan against Communist North Korea and China

- Defended Taiwan’s independence from Communist China

- Integrated the armed forces

- Integrated public schools

- Launched our first satellite into space and founded the organization that would take us to the moon

- Proclaimed “Don’t tread on us” and “Don’t tread on our friends”, rather than just “Don’t tread on me”

For these reasons and others, I’ll be hanging the 48-star flag outside my front door at least through the next election, and probably for a lot longer.

While there are plenty of historical examples showing why this was an imperfect time in the imperfect arc of American history, this period represented what our country could accomplish when we and our allies worked together for a greater good and a better world.

Under this flag my grandfathers defeated fascism, and that’s plenty good enough for me. I encourage all like-minded people to join me in flying the 48 for freedom.*

*Yes, it’s a navy reference

I just finished reading The Great Naval Race by Peter Padfield, an engaging grand-strategy-level overview of the naval arms race between Great Britain and Germany in the years leading up to the First World War.

Interestingly, the book offers little detail about the revolution in battleship design that took place at the turn of the last century. Instead, Padfield highlights the efforts of Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz to achieve his twin goals of deterrence and prestige, contrasting it with British attempts to maintain the Royal Navy’s quantitative (and qualitative) edge.

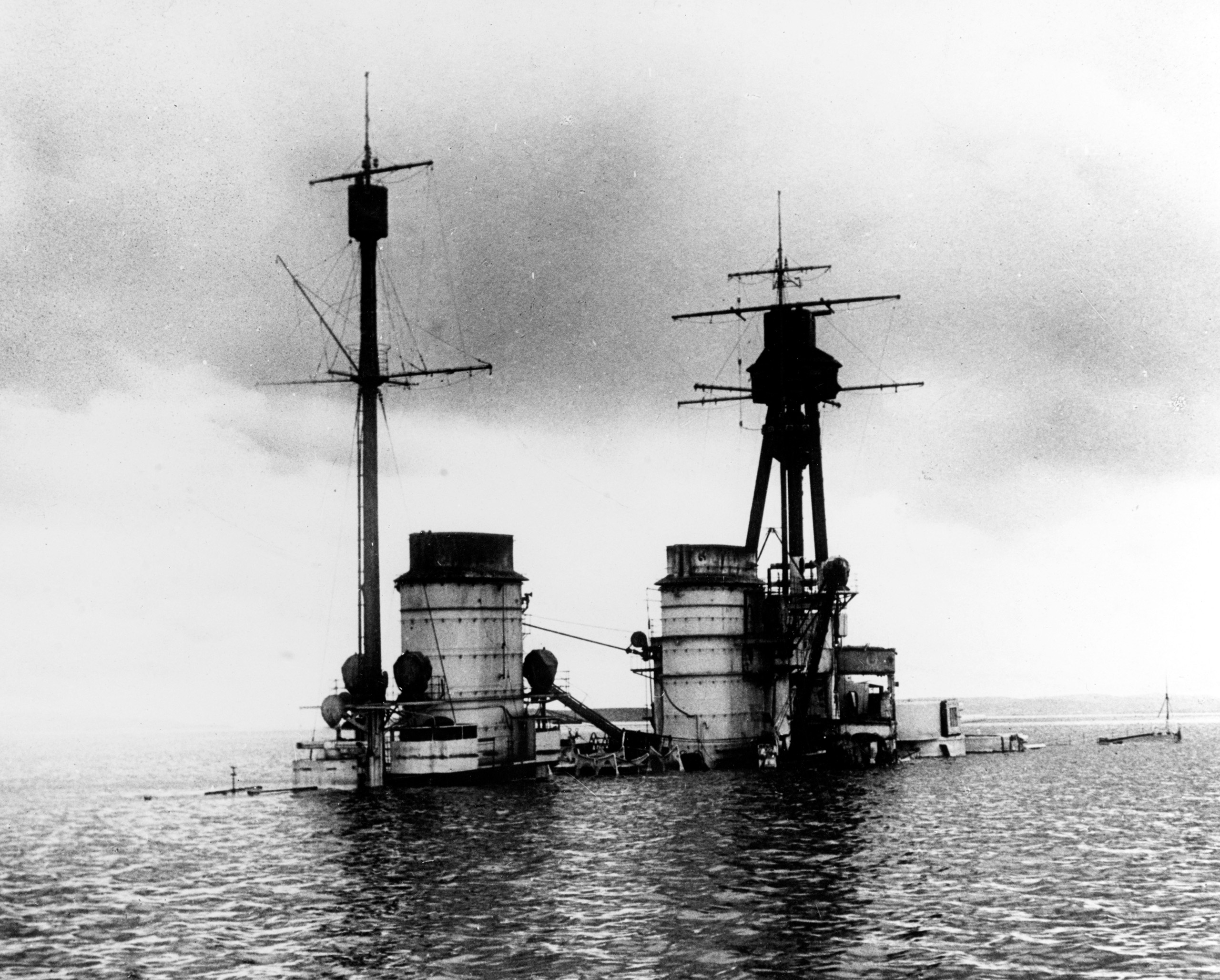

Germany’s breakneck naval construction campaign fueled an unwinnable arms race abroad while enabling forces at home to start the very war Tirpitz hoped to delay or avoid altogether. Any prestige left for the High Seas Fleet after Jutland rests to this day at the bottom of Scapa Flow.

Naval arms races are particularly capital intensive, given the size and complexity of modern warships. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku would argue in favor of continued Japanese compliance with the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty by observing:

Anyone who has seen the auto factories in Detroit and the oil fields in Texas knows that Japan lacks the national power for a naval race with America.

That treaty (and its successors, the London Naval Treaties of 1930 and 1936) softened and postponed, but did not prevent the massive Japanese naval build-up prior to the Pacific conflict in World War II. Isolationism at home prevented the US from matching the Japanese construction pace, even after the war in Europe began in 1939.

With the Two Ocean Navy Act of 1940, the US Navy was finally authorized to more than double in size over the next five years. The fleet that won the war was ordered and building nearly 18 months before our entry into that conflict. But even a century ago, large naval vessels took 2-3 years to build.

As a result, the US Navy’s first year of the Second World War was fought (and the tide turned) with largely inferior and obsolescent vessels, aircraft, and munitions.

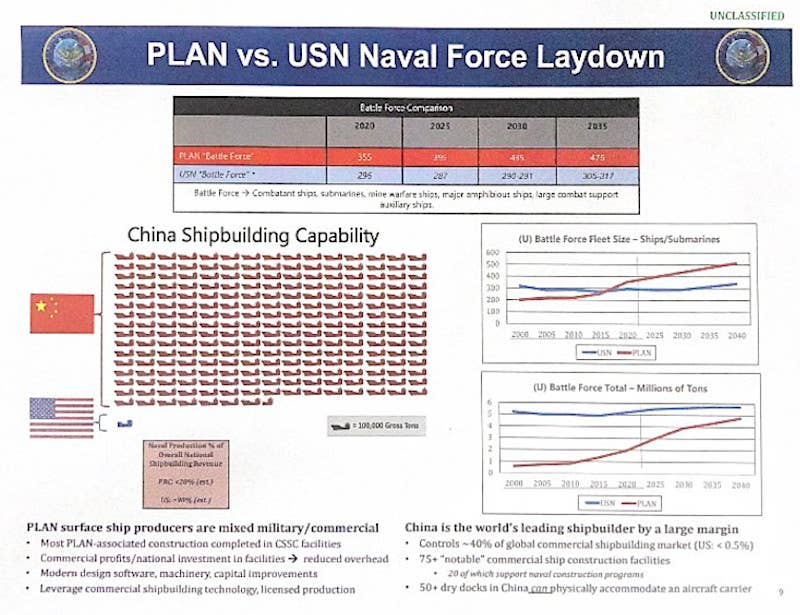

A century later, in very nearly the same part of the world, the situation looks in some ways similar, and in other ways very different:

Somehow I missed this dramatic video of the Artemis I Orion spacecraft reentering the atmosphere after its uncrewed trip around the moon.

I hadn’t really processed the tremendous speeds involved in the spacecraft’s return from the moon until I watched the following animations tracing its flight path using inertial and rotating reference frames.

Artemis I flight path, Earth Centered Inertial. Phoenix7777

Artemis I flight path, Earth Centered Rotating. Phoenix7777

The spacecraft was traveling nearly 40,000 km/h (25,000 mph) when it first entered the upper atmosphere. After using a skip-style non-ballistic reentry to bleed off excess speed (the two deceleration phases are quite apparent in the video) the spacecraft deployed its parachutes for a successful splashdown.

Artemis II is scheduled to take four astronauts back to the moon sometime after September 2025.

For some reason Universal Control wouldn’t allow me to capitalize letters on the iPad Pro that’s connected to my MacBook Air unless I used Caps Lock or let it do auto-capitalization.

The behavior was so strange I thought I was taking crazy pills for a while, but Universal Control is too handy to give up. Thankfully, user _infinideas_ on Apple Discussions had the answer:

On Your iPad:

Go to SETTINGS > Accessibility > Keyboards > HARDWARE KEYBOARDS > turn Full Keyboard Access to ON

** Also (on the same page), SOFTWARE KEYBOARD > toggle Show Lowercase Keys to ON

While the answer was directed at macOS Monterey, the fix (and the glitch) applies to Sonoma as well. It seems like this quirk only affects users of 3rd party Bluetooth keyboards and mice (I’m currently using a clicky Logitech MX Mechanical and MX Anywhere 2S).

As a long-time Synergy (and more recent Logitech Flow) user with a multi-device multi-platform multi-tasking habit, I appreciate just how simple Universal Control is to use, particulary with iPad (since there’s no other option).

Multiple keyboards are a pain, and Universal Control (now) makes it better.

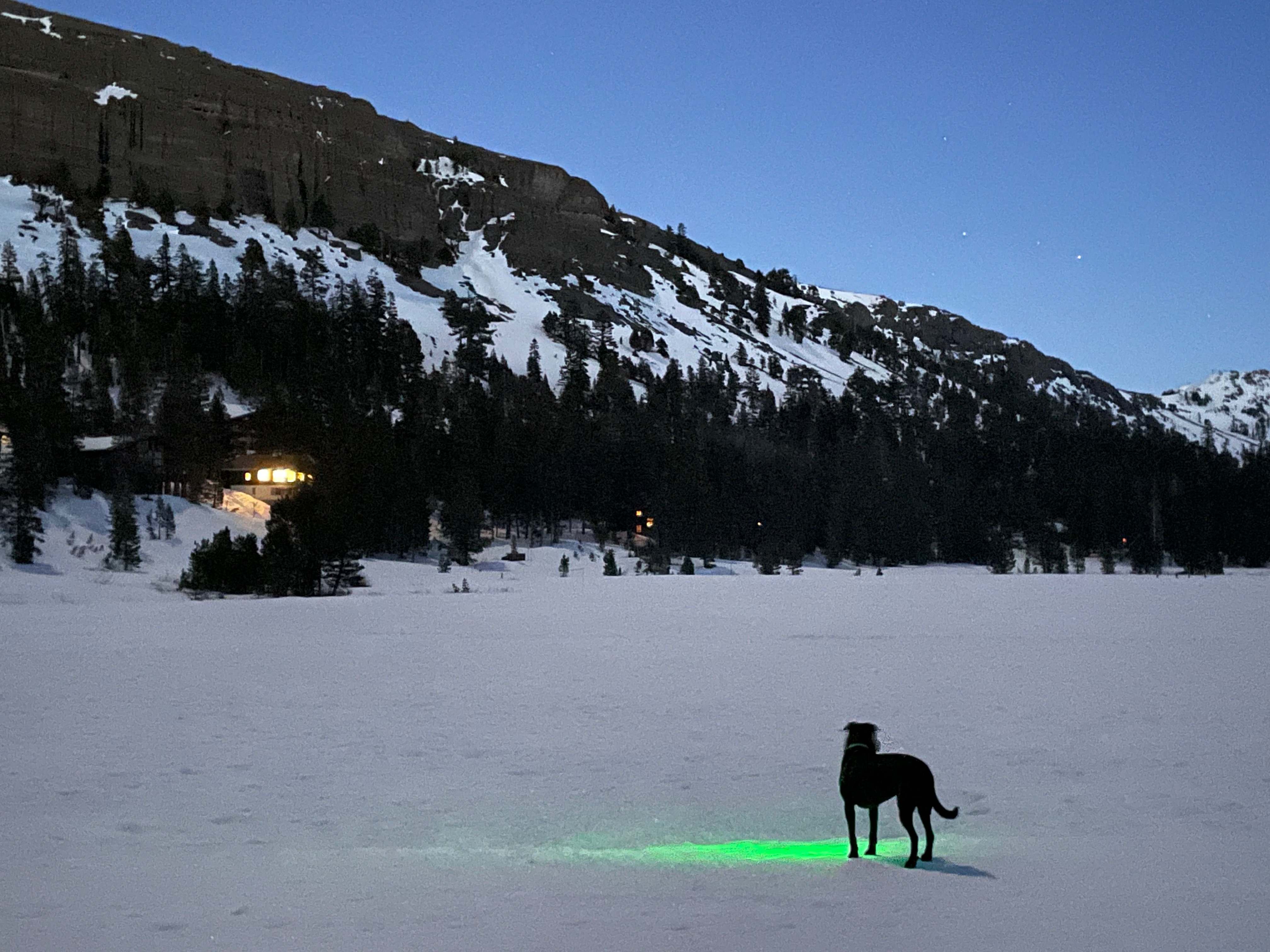

It’s early and my dog and I are the only ones up so far, since my wife likes to sleep in on the weekends these days. We’ve been out for an early morning walk (with too much barking when a neighbor opened their door) the dog has been fed, the coffee has been made (hazelnut light roast) and the fire is lit and burning on its own.

The sky is white now and getting lighter by the minute, although it was dark enough on our walk for me to still make out Antares and a few of the other stars of the Scorpion through the dawn glow.

I’m still trying to figure out how to make my cobbled together paper and digital personal knowledge house-of-cards into a system that will actually work for me in the long run, and frankly I’m stumped. There are so many options, but also it seems that whenever I start using one, a notification pops up on my constellation of devices and I’m suddenly distracted and lose the thread. This is how these devices are designed of course, and they have to be tended like a garden to prevent that from happening again and again.

Paper gives me the opposite of this, at the cost of connectivity and easy search, or at least the promise of those things. It lacks the easy templating available on a computer. Writing is slower than typing by far, and errors are forever. Editing is difficult if not nonexistent.

The longer I struggle with how to solve this dilemma the more I feel that a true solution is impossible. This unsolvable koan has been burning in my life now for a decade or more, and the only solution that keeps coming up is that the answer is whatever you’re using right now. There is nothing else, nothing more, nothing better, nothing worse, just this note, in this medium, again and again, forever.

Perhaps the endless seeking is the poison and simply ending the search – no matter what the choice – is the cure.