I just finished reading The Great Naval Race by Peter Padfield, an engaging grand-strategy-level overview of the naval arms race between Great Britain and Germany in the years leading up to the First World War.

Interestingly, the book offers little detail about the revolution in battleship design that took place at the turn of the last century. Instead, Padfield highlights the efforts of Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz to achieve his twin goals of deterrence and prestige, contrasting it with British attempts to maintain the Royal Navy’s quantitative (and qualitative) edge.

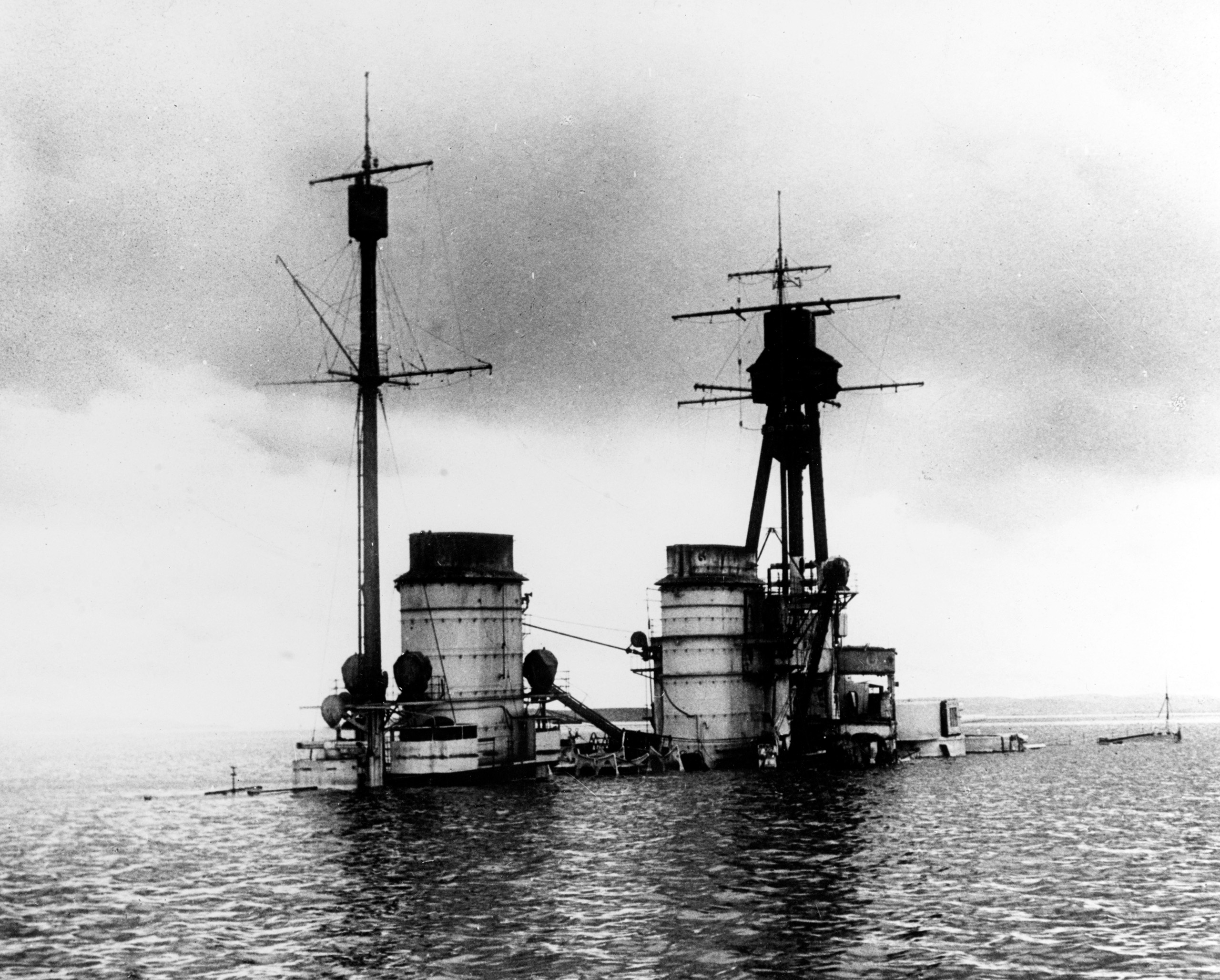

Germany’s breakneck naval construction campaign fueled an unwinnable arms race abroad while enabling forces at home to start the very war Tirpitz hoped to delay or avoid altogether. Any prestige left for the High Seas Fleet after Jutland rests to this day at the bottom of Scapa Flow.

Naval arms races are particularly capital intensive, given the size and complexity of modern warships. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku would argue in favor of continued Japanese compliance with the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty by observing:

Anyone who has seen the auto factories in Detroit and the oil fields in Texas knows that Japan lacks the national power for a naval race with America.

That treaty (and its successors, the London Naval Treaties of 1930 and 1936) softened and postponed, but did not prevent the massive Japanese naval build-up prior to the Pacific conflict in World War II. Isolationism at home prevented the US from matching the Japanese construction pace, even after the war in Europe began in 1939.

With the Two Ocean Navy Act of 1940, the US Navy was finally authorized to more than double in size over the next five years. The fleet that won the war was ordered and building nearly 18 months before our entry into that conflict. But even a century ago, large naval vessels took 2-3 years to build.

As a result, the US Navy’s first year of the Second World War was fought (and the tide turned) with largely inferior and obsolescent vessels, aircraft, and munitions.

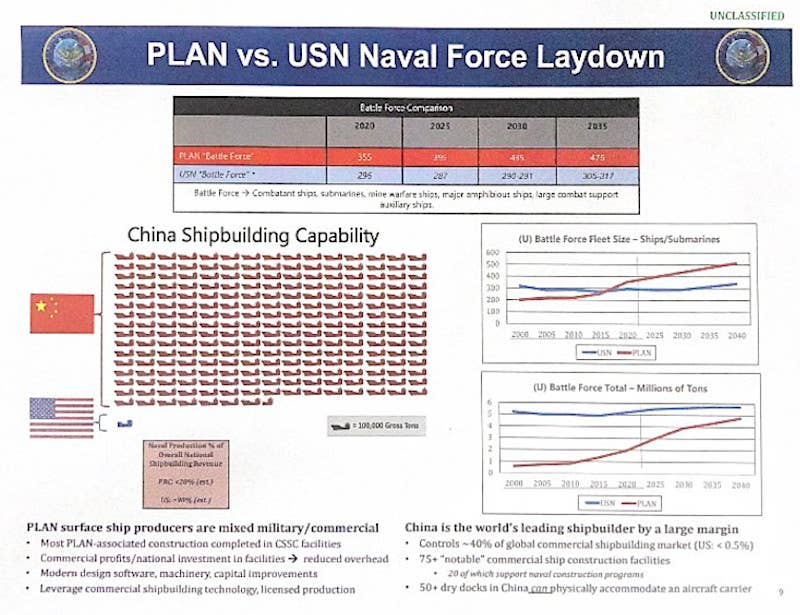

A century later, in very nearly the same part of the world, the situation looks in some ways similar, and in other ways very different: