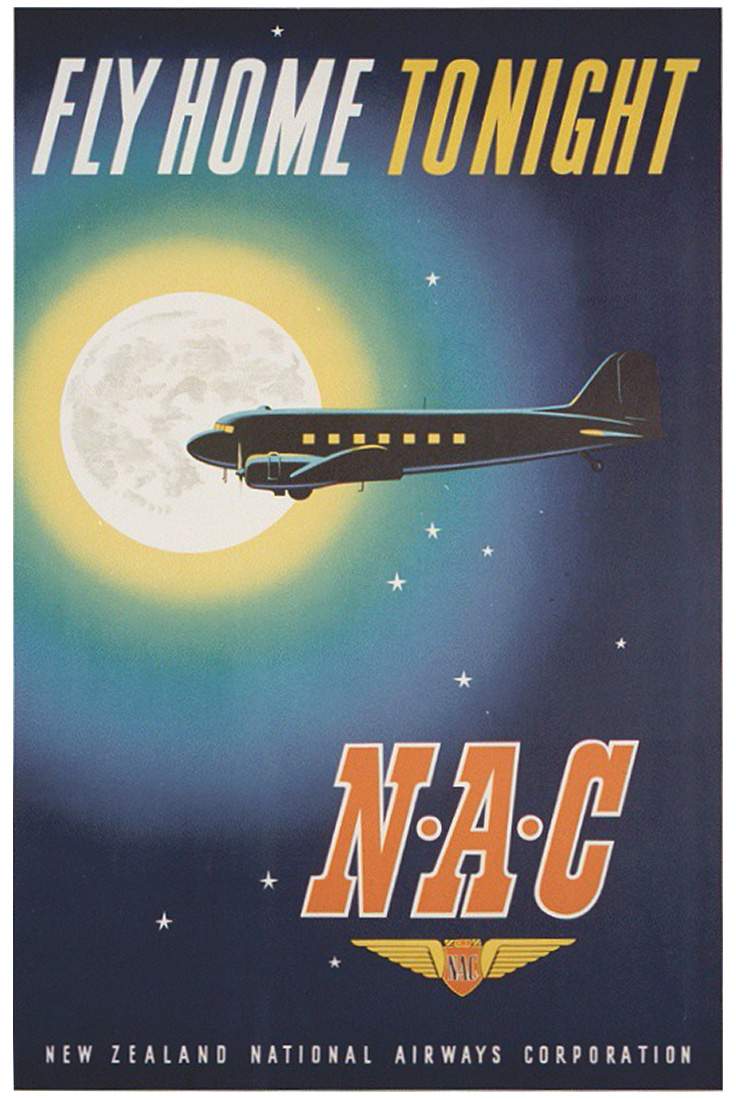

While randomly browsing through Flickr Commons the other day, I stumbled across this beautiful poster for New Zealand National Airways Corporation.

From the San Diego Air and Space Museum.

It’s tough to say when the poster was made. NAC flew the classic DC-3 until 1974, though they were predominantly used in the 1960s. The DC-3 was an enlarged version of the DC-2, originally built as the “Douglas Sleeper Transport” in 1935 for exactly these sorts of overnight flights.

The CEO of American Airlines wanted Douglas to improve on their original design by adding space for 14-16 sleeper berths instead of seats. Crossing the US by air took at least 15 hours in those days, so there was plenty of time to catch some shuteye. Coincidentally that’s about how long it takes to travel to New Zealand from Los Angeles on a modern airliner.

In the end, 21 seats proved more versatile (and profitable) than 16 sleeper berths, and the DC-3 as we know it was born. Apparently there are things about air travel that will never change.

I love the poster’s juxtaposition of the Southern Cross, DC-3, and the full moon, even if the constellation is nearly 60 degrees south of the ecliptic.

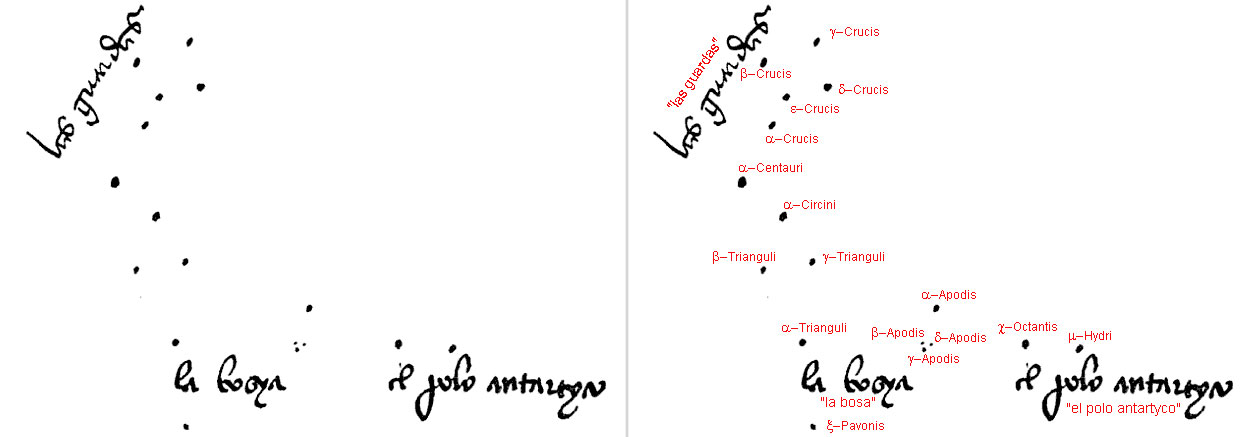

The Southern Cross hasn’t always been so southern. Due to the precession of the Earth’s axis (the effects of which are shown by the large dashed circle in the left hemisphere of the star chart above) the constellation was visible from the middle Northern latitudes as recently as 6,000 BC. If you’re patient enough, the next opportunity to see the Southern Cross from Pittsburgh will come in 20,000 years or so.

While countless others had appreciated it since prehistoric times, the first modern European to accurately depict the Southern Cross seems to have been João Faras, an astronomer and physician of murky origins who sailed with a Portuguese Armada to Brazil in 1500.

João Faras’s map of the Southern Sky, May 1500. Annotations by Walrasiad.

One of Mestre João’s primary tasks was to discover a way to determine a ship’s position by the southern stars. The lack of a southern Polaris (or his unwillingness to wait 7,000 years) made this quite a challenge, given the technology available at the time. The sun proved a better reference, but the constant rocking of the ship’s deck at sea made it nearly impossible for him to get a good reading. Mestre João had more success once they finally reached land, achieving an accuracy to within a degree.

I used to love watching the Southern Cross through night vision goggles. The constellation would rise through the windscreen of my Tomcat over the course of an hour as we flew home from the skies over Kandahar.

Killing time on NVGs as we transit home. Beta and Gamma Crucis are the blurs just to the left of the canopy bow.

Six hundred miles to the south, the USS John F. Kennedy waited for us in the warm, dark waters of the North Arabian Sea. Seeing the bright stars of Crux climbing through the green-tinged sky almost made the night trap worth it.

Almost.