Milky Way

2002.07

“53’s thirteen-five, tapes, Gs.”

“54 thirteen-eight, tapes, Gs.”

Our two Tomcats cruise silently through the green-lit Afghan night, waiting to be needed, waiting to be called. We know in the back of our minds that the call will never come.

Well, maybe not. Someone might need us. Eventually.

Since arriving in the North Arabian Sea three months ago, I've flown over this desert twenty previous times and never fired a shot or dropped a bomb in anger.

I can’t even believe we’re over here… this was supposed to be the good-deal summer Med cruise, right? Who would have guessed we’d ever fly over Afghanistan?

2001.05

A little over a year prior, my squadron (The World-Famous Red Rippers of VF-11) joined the rest of our air wing aboard the USS John F. Kennedy for Fleet Week 2001 in New York City. We’d only been assigned to the JFK for a few months at that point, so it was an excellent opportunity for us to get to know the ship while enjoying the splendor of the Big Apple.

We gave tours during the day, talking about how much we loved our airplane and its homes at sea and in the sky, describing all the tremendous things our jet could do. We took average New Yorkers up to a workstand so they could gaze down into the cockpit. They marveled at its complexity, and we chuckled to ourselves at their naivete.

How could anyone be confused by the PDCP? It’s so simple… You have power switches for the HUD, VDI and HSD. The buttons on the left control your display master modes, the ones on the bottom are for your navigation submodes. The switches control TCS, HUD declutter, PTID repeat, EHSD or ECM override. Nothing to it.

The F-14 Cockpit

It’s easy to forget where you come from. My first flight after getting to the Tomcat community wasn’t in a Tomcat at all, but in the same small orange and white T-34C turboprop trainer I’d flown for my first, halting steps in naval aviation. I remember climbing into its cockpit two years and two different jet trainers later and being stunned by its simplicity.

I remember this thing being so hard… so complex… what happened? Hell, the thing’s only got ten warning lights!

The Naval Aviation training pipeline takes a non-flying officer and–one small step a day–turns him into a Tomcat pilot. It’s intense while you’re immersed in it, but it works.

On day one they demonstrate how to do procedure “A”. Day two, they demonstrate “B” and watch you try “A” for yourself. Day three they demonstrate “C”, you try “B” and practice “A”. On day four they show you how to do “D” while you try “C”, practice “B” and get examined on “A”. You’re now assumed to know “A” cold, and there will be serious repercussions if you have any further trouble with it.

In this manner aviators are made, not born. One step a day, every day for two-and-a-half years.

The citizens of New York welcomed us, our ship and our airplanes almost as museum pieces or a traveling circus.

Come and see it folks! You’ve heard all about it, you’ve seen the movies, now see it with your own eyes! One week only, see daring, borderline-crazy Naval Officers who have forsaken a normal life to ride metal beasts where they throw themselves at each other and great metal ships! Poke them through their cages, they won’t bite! Tour their traveling fortress, and see their steel birds, each the best the 1970s had to offer!

They were kind, asked good questions, and followed our explanations with the slightly puzzled, bemused look of a parent whose child is showing them a city he built out of blocks.

That’s wonderful, honey, I’m glad you are having a good time. That looks like it took a lot of work! Run along and play with the other kids, dear, Mom’s busy right now.

We enjoyed the New Yorkers’ distant hospitality, roamed the city’s bars and clubs in the evening, and appreciated the drinks that were bought for us and the conversations that followed. We weren’t sure they considered us anything more than a bunch of overgrown frat-guys in a crazy flying/hunting club, but we were used to that perception and it wasn’t as far from the truth as it might seem.

Deployment was nine months away, and the more senior JOs had already prepared us to expect the best. A summer cruise in the Mediterranean Sea has been the dream of US Naval Officers since the age of sail. It held promises of port calls in beautiful European coastal resorts, friendly locals, a relaxed atmosphere, perfect flying weather, and short at-sea periods.

The Rippers’ previous cruise, aboard the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, had approached this ideal, with only a brief, month-long stint in the Arabian Gulf to interrupt the fun and make everyone appreciate the Med. We left New York at the end of May 2001 happy we came and ready for workups to begin in earnest.

2001.09

Summer waned, COMPTUEX arrived. The COMPrehensive Training Unit EXercise is a five-week at sea period a few months before every cruise where the carrier battle group learns to work together as a team. Our COMPTUEX was scheduled for the Puerto Rican operations area, and planning for a port visit to Saint Thomas in the sunny U.S. Virgin Islands was already in the works.

The Kennedy was the only east coast aircraft carrier not based in Norfolk, Virginia. Instead its homeport was Mayport, Florida, a source of great happiness for our Jacksonville-based S-3 and SH-60 brethren, but a disappointment for us in the Virginia-based strike-fighter squadrons who couldn’t make the easy trip across town to set up our staterooms before deployment.

A U-Haul was rented and filled, two junior JOs were bribed with promises of no squadron duty for a month, and they set off with our TVs and our stereos on a high-speed trek to Florida. I was a fairly junior nugget myself, so rather than fly a Tomcat to the boat, I rode the “tube”–a military owned version of the DC-9 commercial airliner. We arrived the afternoon before departure, and spent our last night ashore eating Buffalo wings and drinking beer at a local sports bar.

The ship pulled out at 6 AM the next day, and I was where any good junior aviator would be while his surface-warfare counterparts conned the massive ship safely from its pier–in bed. A long day was planned, and our job was to spend the morning setting up our squadron’s Ready Room before the first three of our aircraft arrived that afternoon for carrier qualifications. The rest planned on joining us at a fairly leisurely pace, two a day for the next four days, as the Kennedy and her crew worked back into the challenges of launching and recovering aircraft.

ED and I woke up at seven-thirty, put on our flight suits, and made our way from our stateroom to the Ready Room. Kojak, the only other of our eight stateroom occupants to walk onboard with us, was just getting up as we left and told us to go on without him as he flipped on the TV. Slipping into the back door of the Ready Room so as not to disturb the morning maintenance meeting, we blearily fixed ourselves a cup of coffee and stared at the dozens of bubble-wrapped items waiting to be unpacked.

Suddenly Kojak opened the door behind us and asked, “Is the TV on in here?”

“No,” I answered, “they’re still having their Chiefs meeting, why?”

“I guess somebody flew a plane into the World Trade Center,” was Kojak’s totally unexpected reply. “It was just on the news.”

“The Dogs have a TV,” added ED, and we ducked out the back of Ready Room 3 and slipped down the passageway to our sister squadron’s spaces in Ready Room 4. Opening their door with its large blue “World Famous Pukin’ Dogs” sign, we stepped into a new world.

Several of the Dogs were already standing around the TV in the front of their Ready Room. I wasn’t prepared for the sight. One tower was already burning, and there was a thin curl of smoke rising from the second. The ship shuddered beneath us, and a low but rising vibration shook the deckplates. We were accelerating.

“Hey, another plane just hit the second tower,” said Trigger, one of the Dog JOs, as we walked closer. “This is crazy…”

When Kojak had told us someone hit the World Trade Center I’d immediately thought some small civilian plane had strayed off course or lost an engine at the worst possible time. The damage to the two towers of the World Trade Center pointed to a much bigger aircraft, and our thoughts immediately went to cargo planes or airliners. We bandied about theories for a while trying to understand the incomprehensible, before returning our eyes to the screen in stunned silence.

Meanwhile, our friends at home were watching the same events from their living rooms. With most of their gear either at the squadron or already aboard the JFK, they quickly packed what remained, said goodbye to their families and rushed out the door.

What they found when they reached NAS Oceana was quiet chaos. The line of cars at the front gate stretched two miles, past the Navy Exchange and out onto Oceana Boulevard. A brief conversation with base security personnel got most of them through, often bypassing the traffic by driving on the grass median between the cars. Naval Air Station Oceana was fully locked down.

Basher (the Force Landing Signal Officer for the east coast) also watched the crisis unfold. He got a call minutes after the attack with instructions to report to NAS Norfolk as soon as possible. There, a helicopter would be waiting to take him to the USS George Washington. The aircraft carrier had gotten underway but had no air wing aboard.

No one knew whether more attacks were imminent, so the GW was to steam north to the New York area, while the JFK stayed off Hampton roads to cover the mid-Atlantic and Washington, DC. Since CVW-7 was the only air wing ready to deploy, its two Hornet squadrons would join half of our Hawkeyes and a smattering of other squadrons’ Hornets on the GW, while the Rippers and the Dogs would fly their Tomcats to the Kennedy. Without an air wing, the George Washington had no Landing Signal Officers aboard, so they needed Basher there before they could catch anything but helicopters.

Contrary to popular belief, all the aircraft in a Navy fighter or strike-fighter squadron are rarely “up” (flyable) at once, however happy this would make the average fleet aviator. Usually a third to a half (sometimes even more) are “down” for preventative or contingency maintenance, even on the best days. Squadrons simply don’t have the resources, time or the need to keep all the aircraft ready to fly, and regularly scheduled inspections will often put a jet in the hangar for weeks, if not months.

The exception to that rule is “fly-off”, where the air wing departs the ship after an at sea period. Then every possible means is used to ensure that all a squadron’s jets are flyable (although not necessarily mission capable) to make it home. Compared to our Hornet brethren, a Tomcat squadron tended to have fewer jets available to fly, on average, due to the age and complexity of our aircraft.

The morning of September 11, 2001, the talented Chief Petty Officers in Ripper maintenance control had planned on launching three jets to the USS John F. Kennedy late that afternoon. The rest would trickle out over the next four days until all were safely aboard. Before midday, and within three hours of receiving word, all eleven Red Ripper aircraft were up, armed and ready to fight and fly, if we could find someone to shoot at. The same was true of our sister squadron, the Dogs.

For a Tomcat squadron to have eleven combat capable aircraft at once is highly unusual. For two squadrons to do that was near impossible. For two squadrons to generate those aircraft in three hours was unheard of.

As we steamed farther out to sea, I joined our new CAG paddles Sticky out on the LSO platform. We had already received word that only the Tomcats, some Vikings and a couple Hawkeyes would be coming out today, and until further notice we would continue with our carrier qualifications and remain ready should we be called on to assist in the national defense. The Kennedy was cruising northward at a rapid pace, considering her age and her non-nuclear propulsion. We’d already received word that the first Tomcats would be arriving overhead within a half-hour.

For the first time in history, aircraft carriers were placed under the command of NORAD (deep within Cheyenne Mountain, Wyoming) as a part of the emerging homeland defense structure. The Kennedy and the George Washington were now vital elements of what became Operation Noble Eagle. We would be responsible for intercepting any aircraft crossing the Atlantic that were judged as threatening.

What we were supposed to do after we intercepted them was still being worked out.

A steady stream of jets began arriving around noon, wings bristling with missiles. They would trap, taxi back to the catapult, and launch again, only to return for more traps. After a pilot completed his carrier qualification requirements the aircraft was chained to the flight deck, while he leapt out of the still running jet and another pilot took his place. A few more moments to refuel and it was back airborne, to qualify the next aviator.

Catching a Tomcat

As a brand-new LSO, I didn’t have the experience to wave these jets myself, so I helped in any way I could, usually by “calling the deck”–making sure the landing area was clear of obstructions–or by writing down in our unique shorthand the shouted grades as the controlling LSO called them out. Ripper 205 screamed across the ramp and into the fourth arresting cable, prompting another critique.

“Fair pass… Not enough rate of descent on start, high in the middle, too much power on the come-down in close, high flat at the ramp, four wire!” translated through my pencil into:

205 (OK) NERD.X HIM TMP.CDIC HBAR 4

Another jet followed seconds later with another grade to write, and I gained a growing appreciation for how busy it can get on the LSO platform. There are rarely interruptions in a carrier qualification evolution, so LSOs have to steal breaks whenever they can. I slipped down to our Ready Room during a lull in the action, and got an update on the current situation.

The Pentagon had been hit along with the World Trade Center and it looked like another airliner that had crashed in Pennsylvania might have been on its way to Washington as well, but didn’t make it for some unknown reason.

All airborne traffic in the skies of America–a staggering number of aircraft–had been ordered to land immediately, and while there had been a few scares at first, the only things taking to the air over the continental United States were birds and the US military. I thought instantly about my dad, an airline pilot, and wondered if he was on a trip, trapped in some random airport, unable to get home.

The next few days were filled with uncertainty. There were several briefs on the new rules of engagement that had been hurredly formulated in the wake of the attacks. There was precious little guidance on what to do if an airliner full of innocent people was indeed determined to be hostile.

The George Washington established itself off the coast of New York, as much a show of support as an actual defense of the stricken city. We remained off the Virginia Capes, plowing through unusually high seas and accomplishing as many elements of our exercise as we could without traveling to our Puerto Rican operations area.

I thought many times of the politely bemused New Yorkers we’d met during Fleet Week, and wondered if they would treat us any differently now.

Why should they? We couldn’t have done anything to stop those attacks… We had been caught as far off guard as the battleships in Pearl Harbor. Except this time they went after civilians, with civilians. Welcome to a new world…

A week passed, and our battle group was released to continue with its COMPTUEX training schedule. We left the choppy waters off Virginia Beach for the sunny calm of the Caribbean Sea and the training grounds off Naval Air Station Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico. The simulations we had planned against hypothetical enemies as exercises in the abstract art of waging war from the sea, took on a darker, more realistic and somber tone.

War against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan was becoming a greater and greater certainty and we were convinced that the Carrier Air Wing Seven / USS John F. Kennedy team would be in the thick of it. Our summer Mediterranean dream cruise looked like it was turning into a winter combat cruise in a new and unfamiliar land, and we were more than willing to make the trade. We wanted payback as much as anyone and prepared ourselves to be sent straight from the Caribbean to the North Arabian Sea to join the USS Enterprise, already waiting off Pakistan.

But there were already vessels on the way, and it was decided that we should continue our training cycle and ready the ship for a January cruise, a few months earlier than planned. As we watched the first strikes of the war over the bars of our Caribbean playpen, we concentrated on finishing our exercise and returning home as soon as possible. Our planned port-call in the Virgin Islands was cancelled for force protection reasons, and after forty-five straight days at sea, the Kennedy battlegroup returned home to find a changed America.

Security at the base reached levels it had never seen before, as gates were closed and barricaded with a few heavily guarded exceptions. There were members of the National Guard in camouflage and brandishing assault rifles at Norfolk International Airport. We got used to mile-long traffic jams at the Oceana front gate and having to show our military ID nearly everywhere. After a short Thanksgiving break the air wing headed to NAS Fallon in the high Nevada desert, for a shortened syllabus in integrated strike warfare. As we watched the new Afghan war play out on TV, everyone hoped they’d save some targets for us. The war seemed to be going better than expected in its first few weeks, and the inevitable cautions against “another Vietnam” seemed premature and alarmist.

We readied ourselves for a January deployment, but along the way we ran into the CVW-7 curse. Carrier Air Wing Seven, to which the Rippers belong, has been jokingly called “Peace Wing Seven” by scores of junior officers within and often outside the air wing.

It’s rumored that this reputation has even reached the Pentagon, although you never can be quite sure about those things. We’d received this dovish moniker because for the last three decades, Air Wing Seven had missed every major military operation involving the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East–often by a matter of weeks–arriving just after, or departing just before hostilities break out. While we would have loved to attribute this unfortunate sense of timing to our air wing’s fearsome combat reputation, most of the JOs chalked it up to pure chance and the malevolent hands of fate.

Despite our best efforts to the contrary, the curse struck again.

Our departure was delayed nearly a month while badly needed repairs were finished on our long-neglected aircraft carrier. The war cooled. In February our hopes were lifted as Operation Anaconda flared in northern Afghanistan, but the situation quieted again and stayed that way once we arrived. Even India and Pakistan, who were rattling their now nuclear sabers at each other, had resumed a dialogue. The curse had struck again.

There were wry rumors that a new Middle East peace proposal would require CVW-7 to be permanently stationed off the Israeli coast, to spread our waves of peace and brotherhood through that hotly contested land. In the meantime we turned circles in the sky over a dark, quiet Afghanistan, waiting to be called.

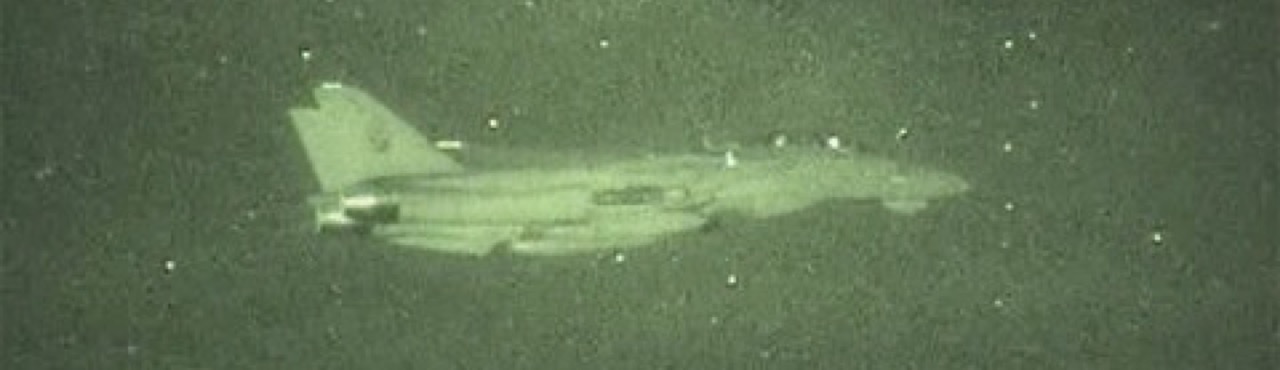

Me on NVGs

2002.07

“Twelve eight, tape, g,” is my call into the darkness.

“Twelve seven, tape, g,” is Lik’em’s quiet reply. He’s been flying night formation on goggles for over two hours now, and must be getting tired. Our Tomcat’s autopilot is next to useless and usually broken, so we have to hand-fly every minute of the four to six hour flight.

“You wanna take the lead for a while?” I ask.

“Sure, 54 has lead right,” as 201 slides abeam.

“54, you’re lead right, smash off, lights dim.”

We swap light configurations and his blinding glow dims to a bearable level. I drop back and cross under his aircraft in the darkness, pausing to look at the bright green glow of his engine cores through my goggles. I continue across, coming to rest in a loose cruise formation on his right side and Lik’em begins our next turn in holding.

The night is calm, and despite a total lack of moonlight, it is easy to follow the other jet through its wide arc. The pulsing red glow of our anti-collision light illuminates the underside of Ripper 201, and gives me a visual reference. I move a little closer and his airplane gets bright enough to read the NAVY on his right engine, with a fuzzy green VF-11 on the ventral fin just below.

Through my goggles, the mountains below us are shadows in the starlight, drifting by like green icebergs waiting to sink any aircraft foolish enough to wander too close. But tonight we are safe at altitude from any threats, natural or manmade, and however much the natural world around my airplane reminds me of Fallon, Nevada, our “war” here is much, much different.

Far less challenging and far more quiet.