Aaron Mahnke is a talented freelance designer and podcaster. He also keeps busy writing about freelancing and productivity in his book Frictionless Freelancing and related blog.

In his recent post Debt he discusses falling short of time and how hard it is to get time back once it’s lost.

Sometimes things don’t go according to plan. I recently spent my Sunday morning sitting in an auto repair shop having a flat tire replaced. It was not something I had scheduled, though.

So, how do we recover from emergencies like this? When it’s a financial emergency, we tend to borrow the funds and then work hard to pay it back. But where do we “borrow” time?

His recommendation (build a cushion of extra time and plan for things to go wrong) reminded me that we do exactly the same thing in military aviation.

When strike planning, nearly everything revolves around “TOT”–short for Time-on-Target. In an ideal scenario, all the airplanes in a strike would deliver their ordnance so it arrives at the same predetermined time. Among other things, this minimizes the opportunity for a defender to react and limits the amount of time you’re exposed over a hostile target area. Doing this successfully requires a great deal of coordination before the flight, then discipline maintaining speed and heading when airborne on the strike route.

Everything in the strike is constructed so a dozen or more airplanes arrive at their release points at just the right moment. Naval aviators learn these skills early in training and practice them their entire careers.

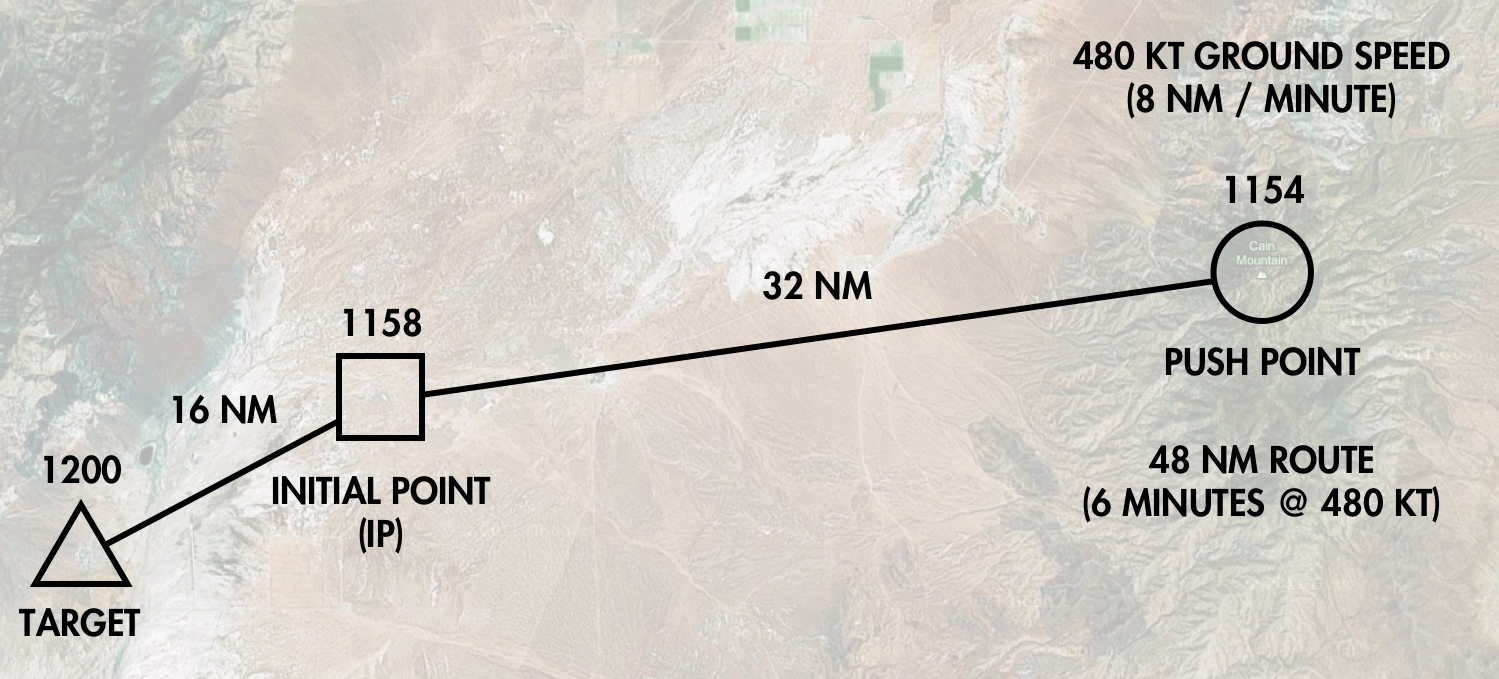

Let’s look at an example. Say our TOT is 1200 noon. The strikers plan to fly 480 knots (nautical miles per hour). The total route length for a simple route from the push point through the initial point (IP) to the target is 48 nautical miles. That means it should take around six minutes from push to target.

To be on time, we should leave at 1154. If we do everything perfectly, we get to the target right at our TOT. To make it easier to visualize, I’ve drawn it all out on the chart below.

Basic Strike Route

That’s fine for Merlin, I hear you say, but what about the real world? How do you plan for contingencies?

Surface-to-air missile sites, enemy fighters, or just plain poor flying can put you “behind timeline” before you know it. Sometimes you can fly faster, but that burns more fuel. When you’re down to minutes, a strike can get far enough behind that no amount of acceleration can save it.

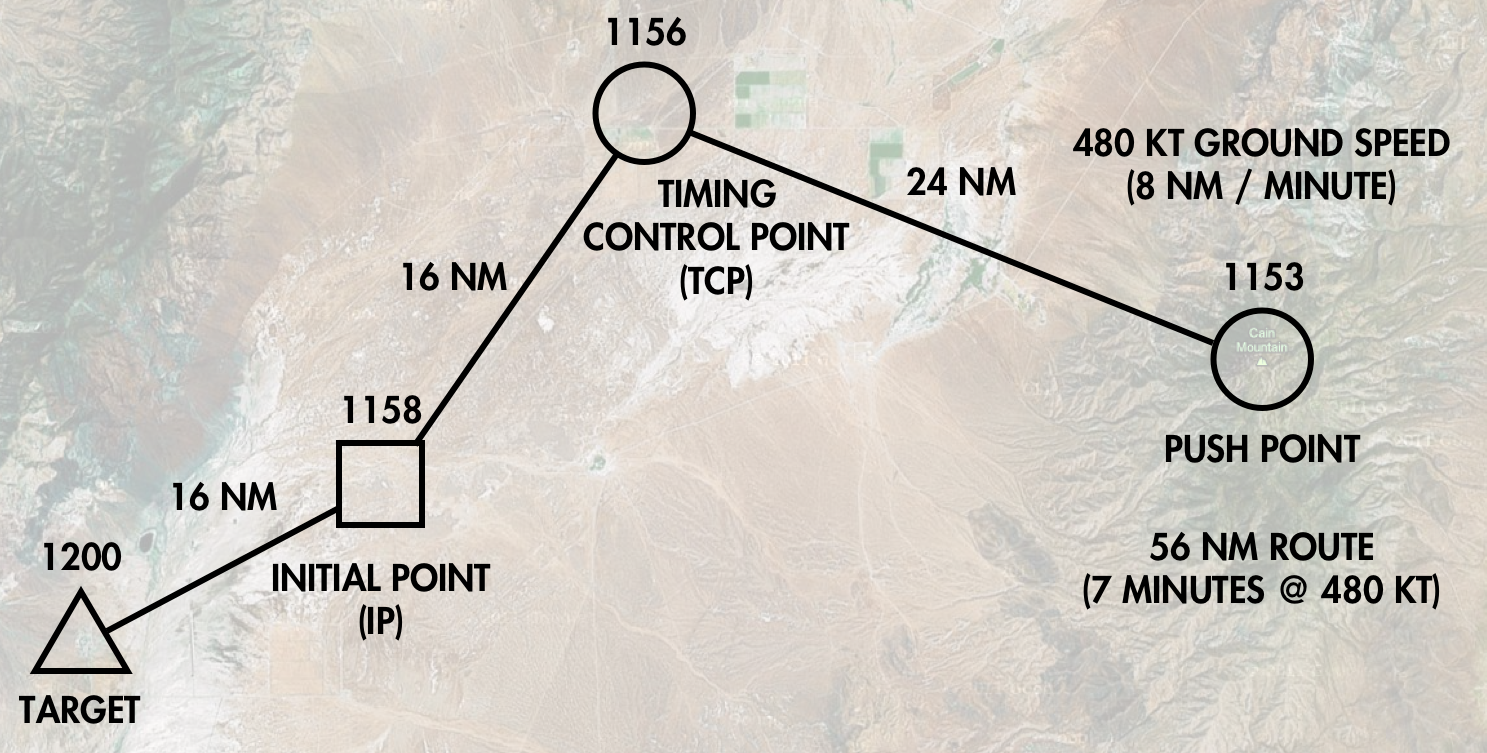

The solution is to add a Timing Control Point (TCP) to the strike route, increasing its length with a dogleg and giving us a corner to cut if things go wrong. The route below is now eight miles longer, allowing an extra minute of slop if we need to make up some time.

Strike Route with TCP

If we’re behind, we skip the TCP and go straight to the IP. A minute may not sound like much, but it’s an eternity to a jet on a strike route.

So why does this matter?

Time management is a universal problem. Look outside your everyday world, and you might find somebody has faced a similar challenge in a way that inspires you to think about it in a different light. How many times have you left just a bit early in case there’s traffic on your way to work? The TCP on a strike route follows from the same principle.

While it’s probably not the right move to put a dogleg into your assault on the buffet table tomorrow, planning for friction before you even start your next adventure can be of real benefit when things start to go wrong. And something always goes wrong.