Reports today state that North Korea has moved two medium-range ballistic missiles onto mobile launchers at their eastern launch site. Most say the missiles in question are probably the BM-25 Musudan, a medium-range weapon derived from Russian submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) technology. In this post I’m going to take a closer look at the Musudan and what we know about its history and capabilities.

The majority of my information comes from an excellent 2012 study of the North Korean nuclear missile threat by RAND's Markus Schiller. If you're inclined to a deeper study of this topic as well as a detailed breakdown of our confidence level in each piece of data, I highly recommend reading Mr. Schiller's article in full.

A Tale of Two Musudans

There’s a real potential of confusion when referring to the BM-25 Musudan ballistic missile, for Musudan-ri is one name for North Korea’s eastern launch site, otherwise known as the Tonghae Satellite Launching Ground.

Musudan-ri Launch Site

It’s a rough and mostly undeveloped facility, which looks to have been superceded by the new and more robust Sohae Satellite Launching Station in a secluded area on North Korea’s west coast. From a geopolitical perspective, launches from Musudan-ri are important because they tend to go towards (or even over) Japan.

The History of the BM-25

Initial reports of the missile that would become known as the BM-25 Musudan surfaced in 2003, but it wasn’t seen in public until it was shown at an October 2010 parade. The missiles, which appeared to be mounted on a hacked Russian Transporter-Erector-Launcher (TEL) were almost certainly mock-ups.

Still, even a mock-up is enough to give some useful information about its design, which in this case closely resembles a stretched Soviet R-27, known to NATO during the Cold War as the SS-N-6 Serb.

K219, a Soviet Yankee-class Submarine in Distress

The R-27 was designed to equip the first batch of Soviet Yankee-class ballistic missile submarines. While an excellent missile that approached the performance limits of a liquid-fueled rocket of its size, its propellants were highly volatile, leading to the 1986 loss of K219 northeast of Bermuda.

It appears that North Korea may have substituted an alternate oxidizer for the Musudan, but indications are that it’s no less volatile or corrosive. Additionally, the missile is unlikely to be much stronger than its predecessor without accepting a major reduction in range.

The fragility comes from the missile’s roots as a submarine launched weapon, where it was stored in an environment much less jarring than it experiences riding atop a TEL on unpaved roads. It means the Musudan must be transported before it’s fueled (which is complicated, dangerous and time consuming). Additionally, the missile probably can’t stay in a launch-ready state for much longer than a few weeks.

Musudan Performance

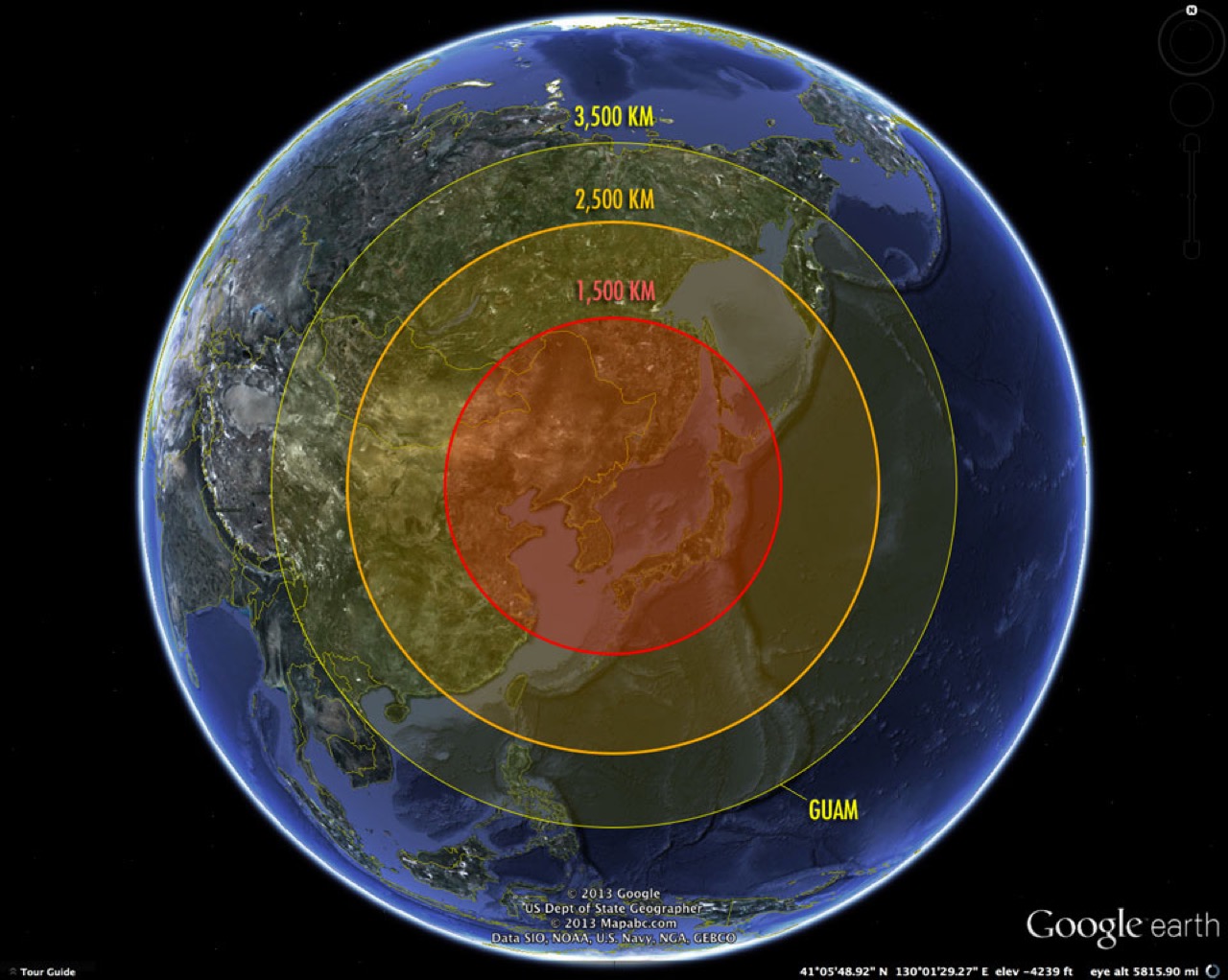

The Musudan is longer and has a smaller payload than the R-27 which should result in a bit of a range improvement. Current news reports state its range as anywhere from 2,500-3,500 km, which compares favorably to the R-27 at about 2,000 km.

Schiller backs up those numbers in his report with the caveat that the Musudan must share the same quality metal and construction as the R-27. If the North Koreans have reconfigured or reverse engineered it using heavier but simpler materials, range could drop as low as 1,000-1,500 km.

A quick analysis shows that a Musudan launch could theoretically reach a substantial part of the Western Pacific, but if materials issues come into play this is likely reduced to South Korea and Japan.

Musudan Range

For comparison, here are some approximate distances to US points of interest:

- Guam: 3,350 km

- Attu: 3,500 km

- Anchorage: 5,600 km

- Honolulu: 7,000 km

Is the Musudan a credible nuclear threat?

Despite all the reports, no public source has ever provided pictures of an actual, flight-ready Musudan. While Jane’s has estimated potential deployment of up to 50 of these missiles, there are no sources for those numbers.

Most importantly, the missile itself has never been flown. That’s right, never. Not once.

Additionally, the North Koreans have yet to demonstrate a weaponized nuclear capability, much less one that can withstand the crushing aerodynamic loads, acceleration, and vibration found at the business end of a missile. Putting a Musudan on target is difficult. Building a light nuclear warhead that can function when it gets there is even harder.

If you were about to start a nuclear war, would you lead off by putting an untried warhead on an untested weapons system, then put that supposedly mobile weapons system in a prominent, easily observable location and take great pains to prepare it in the open, before firing it in anger?

Neither would I.

All signs point to this as preparation for another pure missile test which North Korean leadership can use as an internal justification to declare victory, deescalate, and return to the bargaining table. This has happened before.

The question of whether the North Korean leadership is capable of pulling off this sort of brinksmanship without a serious miscalculation or inadvertent provocation is outside the scope of this article and beyond my ability to forecast.

But I sure hope so.